On Which Side of the 49th Parallel are the Greenbacks Greener?

Canada vs. the United States

Note: You may notice a different format for this newsletter. I decided to migrate my seanbutler.ca site over to Substack. The main reason is that I’ve found that my other Substack, Farmer’s Table, where I write about food and farming (subscribe if you haven’t already!), is more discoverable by being a part of the Substack network. If you took out a paid subscription to the old site, first, thank you! And second, I’ve given you a comp to this new site for at least as long as your old subscription. If you like what you read in this newsletter and would like to support my work with a paid subscription (as well as gain access to subscriber only posts), it’s only $5 a month or $35 a year, and would be greatly appreciated. I lot of time and care go into these articles. Thank you!

Canada has always been a country in search of a national identity. Living in the shadow of its much larger neighbour, and sharing with it a language and common cultural origins, it has struggled to discover what it is about itself that makes it unique and worthy of building a nation for. But it has been a mostly introspective struggle; we hand-wring internally about who we are, but rarely have outside forces tested us.

In 1812, before we were a country, the young American republic did test us, and we repelled their invasion – albeit with British troops and First Nations doing most of the heavy lifting. A half century later, with the US Civil War newly won by the north, Alaska just purchased, and talk among Union leaders of perhaps putting their large army to further use fulfilling Manifest Destiny, several British provinces decided they’d better join forces and form a country, resulting in the Canadian Confederation of 1867. Canada at its inception was born out of a rejection of being American.

Canada has enjoyed largely friendly relations with its cousin to the south since – that is until the newly reelected President Donald Trump started openly musing about making it the 51st state. His words – and the trade war he has initiated with the apparent intention of paving the way to annexation – have lit the fire of a long-dormant Canadian nationalism, bringing the self-indulgent navel-gazing of wondering who we are into the realm of existential imperative.

Mark Carney, who recently rapidly ascended to the prime minister’s office, largely because he’s widely seen as the person best qualified to oppose our newly belligerent former ally, addressed in his victory speech what he sees as the main differences between the US and Canada: “In America, health care is a big business. In Canada, it's a right. America is a melting pot. Canada is a mosaic. In the United States...they don't recognize First Nations. And there will never be the right to the French language.”

So there it is: free health care, multiculturalism, indigenous reconciliation, and bilingualism. These are the four pillars, according to our new leader, of Canadian identity – all in opposition to American identity. The last three all have to do with bringing disparate cultures together under one identity, while still respecting their differences – a tightrope walk that Canada has arguably walked better than any other contemporary nation state. (Although one could also argue that the “bringing together” part has atrophied while the “respecting the differences” part has grown stronger, to the detriment of our national self-identity.) Our identity is the self-referential act of trying to bring multiple identities together into a “mosaic” rather than a “melting pot”. The one thing that does unite us – universal free health care – is actually not that unique in the world; most developed nations have it. It is only the Americans, exceptional as they are, who don’t – thus providing us with a useful foil for our national identity.

The man Carney just replaced, Justin Trudeau, struggled to define the identity of the country he led for a decade, even going so far as to claim that Canada was without any “core identity”, and suggesting that we could be the “first postnational state”. (His father, Pierre Elliot Trudeau, was much more ambitious in his nation building, consciously constructing a self-identity around two of those pillars – multi-culturalism and bilingualism – while repatriating the constitution.)

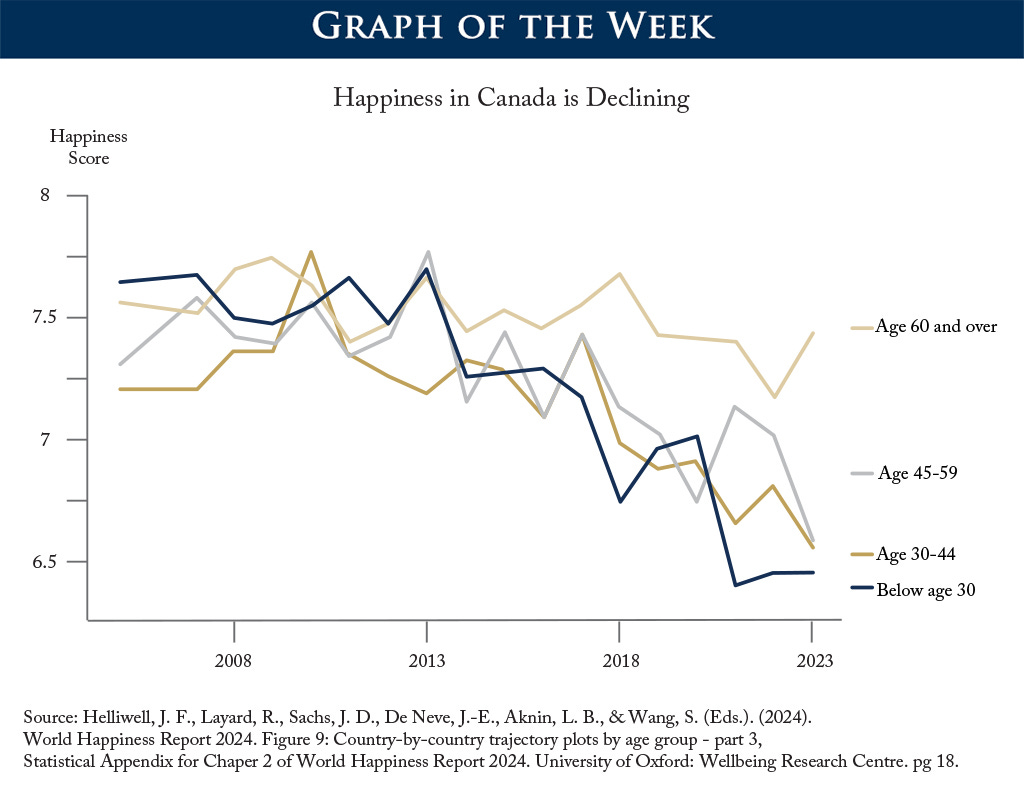

The Justin Trudeau decade was not a good one for Canadian identity, or Canada generally. Those who reported being “very proud” of their country dropped from 52 percent to 34. Our real GDP per capita is at the same level as ten years ago. And our happiness ranking compared to other countries slipped from 5th (our best showing) to 18th (our worst), making us one of the “largest losers”, according to the most recent World Happiness Report.

Perhaps sensing weakness, Trump decided to pounce. But in so doing, he has proven that Canadian nationalism, though weakened, still has life to it. If there’s one thing we are certain of, which has always been our strongest bond, is that we do not want to be American. From right-wing Pierre Poilievre to left-wing Elizabeth May, and from libertarian Alberta to socialist Quebec, opposites came together in a sound rejection of that idea. Since the Trump threats began, pride in Canada has rebounded by 10 percentage points, a grassroots buy-Canadian movement has swept the land, and polls show that 90 percent of Canadians don’t want to join the US.

Nationalist not all

But there is one group who entertain the idea more than most. In a January Ipsos poll, a whopping 43 percent of those aged 18 to 34 said they would vote in favour of joining the US, provided they were offered full citizenship and conversion of assets to US dollars. Only 17 percent of those 55 years and older said the same.

What’s driving this dissatisfaction among younger Canadians? Élie Cantin-Nantel, writing in The Hub, and a self-described member of Gen Z, spoke to other members of his generation, and basically chalks it up to three beliefs about life in the US: that incomes are higher, housing and other goods are cheaper, and taxes are lower.

It is true that, when measured in GDP per capita, Canada is far behind the US, and the gap is widening. In 2002, Canada’s GDP per capita was about 80 percent that of the US’s; 20 years later it had fallen to 72 percent. Canada is also falling behind other peer nations: Canada and Australia had equal GDP per capitas in 2002, but by 2022 Canada’s had fallen to 91% of Australia’s. Canada is still higher than New Zealand and the UK, but both those countries have been catching up.

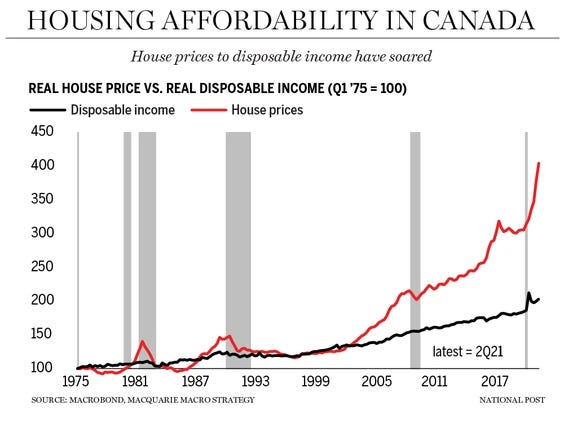

The advantage continues for the US when it comes to the cost of buying a home. The average home in Canada costs $465,000 USD ($668,000 CAN), while the average sale price in the US is $357,000 USD. Visual Capitalist has a great graphic showing how much housing prices have increased in various OECD countries relative to income since 2015. Canada has had the second-highest increase, at 37%. (The US didn’t fare much better, though, coming in third at 30%.) Young Canadians are understandably furious about being essentially shut out of the housing market, and they see the US as a place where they stand a better chance of achieving the middle class dream of home ownership.

The picture is more complicated when one looks at the cost of other goods. It’s well known that staples like gas and groceries are cheaper in the US, but across the spectrum, goods in Canada actually cost about 10% less than in the US. However, when you look at purchasing power – which combines income with the cost of goods – the US is 6th in the world, while Canada is 23rd. So stuff is a bit cheaper in Canada, but we have a lot less money to buy it with.

The tax picture is even more complicated, with much depending on which state or province you live in and where you fall on the income scale. The US’s lowest federal income tax rate is 10%, compared to Canada’s 15%. But the US’s highest rate is 37%, compared to only 33% in Canada. However, the US has more deductions for high earners. Then there are state and provincial income tax rates, which range from 0% to 13.3% in the US, versus 4% for the lowest earners in Nunavut to 25.75% for the highest earners in Quebec. Finally, sales taxes run the gamut from 0% to 7.25%, depending on the state, compared to 5% to 15% combined provincial and GST taxes in Canada. Looking at these rates, it does appear that for most people, the tax burden is less in the US.

A common metric for how much countries tax their citizens is to look at the tax-to-GDP ratio. Canada collects 33% of its GDP in taxes, while the US collects only 28%, suggesting that in the aggregate the tax burden is indeed heavier in Canada.

Looking at all these numbers, it would seem that young Canadians have a point: life in the US, at least speaking from an economic point of view, does seem better. This could explain one reason why young Canadian’s happiness has slipped so much in recent years: in the World Happiness Report, older Canadians actually ranked 8th in the world, while those under 30 were way down at 58th. The only countries to report a worse decline in young people’s happiness were Jordan, Venezuela, Lebanon, and Afghanistan.

Clearly, something is rotten in the state of Canada for young people. The kids are not alright. Who can blame large numbers of them from showing little loyalty to the country they grew up in?

Is the grass really greener south of the border?

While I have no desire to diminish their very real concerns, especially when it comes to the out of control housing market, I still have a nagging doubt. Even through the narrow (but understandably important) lens of economic well-being, would most young Canadians actually be better off in America? Our taxes are higher, sure, but those taxes fund free health care and other benefits not available in the US – benefits that make life more affordable for Canadians. What would a more holistic view of affordability look like in a head-to-head comparison of the two countries?

When it comes to health care, the US spends double per person what Canada spends, and yet gets considerably worse results. In a comparison of 11 high-income countries, the US ranked dead last – by a wide margin. In fact, it ranked so far behind the other countries that it had to be excluded from the average so as to not skew the results.

However, Canadian’s pride over how much better our health care system is than the US’s hides a truth that, when you zoom out from our North American backyard, quickly becomes evident: the US’s system is the only one we’re better than. Canada ranks 10th in this list. Hardly much to brag about.

Still, Americans without employment-based health insurance – which is about half of them – can expect to pay around $477 USD a month on average to give them some coverage in case of medical needs, while still facing the stress of possibly being denied coverage should they make a claim. 56 million Americans struggle with medical debt, and being unable to pay one’s medical bills is the number one cause of bankruptcy in the US.

In addition to free health care, prescription drugs are nearly three times cheaper in Canada on average, thanks in large part to the Canadian government negotiating maximum drug price with pharmaceutical companies, and plans are in the works for a national pharmacare plan that will cover the cost of many drugs (Quebec has had a partial one for years). A national dental care plan is also currently being rolled out, meaning lower income Canadians will no longer have to pay to have basic procedures done to their teeth.

Perhaps the most telling statistic that sums up health is life expectancy; Canada is best in the Americas (and 19th in the world), at 82.88 years, while the US sits at 48th, at 79.61 years – worse than Albania.

What other major factors affect affordability? Well, think about the common phases of life: you get an education, you find a job, you have kids, you retire. Let’s look at each of these.

Education

Canadians can expect to pay about $30,000 CAN (around $21,000 USD) in tuition fees for a four-year university degree. Universities do not charge out-of-province students more (with the new exception of Quebec; in-province university students in Quebec pay the lowest tuition in the country: about $20,000 for four years.) The same degree costs on average more than double – $44,000 USD – at an in-state public college in the US, with that figure rising to around $100,000 if you wish to study out-of-state, or $175,000 if you go to a private college. A four year degree at Harvard, without grants or scholarships, will set you back $236,000.

Employment

The US often has a lower unemployment rate than Canada – it is currently at 4.1, versus Canada’s 6.6. However, those who have given up search for work are not counted in this statistic. A more accurate measure might be the labour force participation rate. In Canada, 70% of those aged 15 to 64 have a job; in the US, it’s 67%. This number would seem in indicate that unemployment is actually lower in Canada.

And in Canada, when you do find yourself without a job, there’s a better social safety net to catch you. (This could partly account for the lower unemployment rate in the US, as workers face greater pressure to accept any job they can find, at lower wages: the federal minimum wage in America is a measly $7.25 USD; it’s $17.30 CAN in Canada.) Employment Insurance in Canada typically lasts for 45 weeks, while in the US, benefits vary by state, but are generally to a maximum of 26 weeks. And unlike in Canada, there is no federal paid sick or parental leave program in the US. In fact, the US is in a select club of only seven countries in the world who offer no paid parental leave, rubbing shoulders with countries like Papa New Guinea, Micronesia, and Tonga.

The US continues its outlier status when it comes to federally mandated paid vacation time. It is one of four nations in the world (hello again Palau, Nauru, and Micronesia!) who don’t force employers to give their workers at least a few paid days off. Canadians get a minimum of two weeks, or vacation pay in lieu.

One final stat, from the OECD Better Life Index: 10% of Americans work “very long hours”, compared to only 3% of Canadians – probably reflecting a sizable underclass in the US forced to work long hours at miserable pay just to make ends meet.

Childcare

In addition to the parental leave Canadians are entitled to, the Canada Child Benefit, brought in in 2016, pays a maximum of between about $6,500 and $7,800 CAN per year per child ($4,600 to $5,500 USD), depending on the age of your child and your income. Having reduced child poverty by 40%, it is a significant positive legacy of the Justin Trudeau years.

In the US, the Child Tax Credit, which did pay a refundable amount up to $1,600 USD pre-Covid, was raised to a maximum of $3,600 during the pandemic, lifting millions of kids out of poverty. But it was not renewed, and is slated to decrease to $1,000 after this year.

Another positive legacy of Trudeau is his federal child care program, which aims to expand the standard set in Quebec of $10-a-day daycare across the country. Speaking as a Quebecker, who got to enjoy affordable daycare when my son was little, this was a hugely helpful benefit. We paid about $2,500 CAN ($1,700 USD) a year for our son to go to a delightful home daycare. I feel bad for Americans, who can pay up to ten times that amount: between about $5,300 to $17,000 USD a year per kid.

Retirement

When it comes to government pensions, both the US and Canada have similar systems: equal pay-cheque deductions are made from employees and employers and benefits are paid out at retirement according to how much was contributed over a person’s working life (known as Social Security in the US and the Canada Pension Plan north of the border). That said, without reform, the reserve that funds Social Security will be depleted by 2033, resulting in a reduction of payouts to retirees. The CPP (or QPP in Quebec) on the other hand, is projected to be sustainable for at least the next 75 years.

In addition to the CPP, Canada also overlays two other payments for seniors: Old Age Security and the Guaranteed Income Supplement. OAS pays about $8,500 to $9,500 a year to every Canadian over 65 with an income of less than about $150,000 – a kind of guaranteed income for seniors. In addition to that, lower income seniors receive up to about $12,000 a year from the GIS. As a result, the poverty rate for seniors in Canada is only 4.7%; it is over 10% in the US.

OK, that was a lot of numbers. But who wins?

So when you factor in costs and benefits around health, tuition, employment, child care, and retirement, the lower income/higher taxes picture in Canada appears to be mitigated by a whole lot of government policy and benefits. But does it tip the balance in Canada’s favour? Is the economic reality for Canadians still worse, the same, or better than that for Americans?

To try to answer that over-arching question, I searched high and low for some indicator that takes into account all these factors: income, taxes, costs, and benefits. I couldn’t find a perfect answer, but household net adjusted disposable income gets close. It adds up all the after tax “income from economic activity (wages and salaries; profits of self-employed business owners), property income (dividends, interests and rents), social benefits in cash (retirement pensions, unemployment benefits, family allowances, basic income support, etc.), and social transfers in kind (goods and services such as health care, education and housing, received either free of charge or at reduced prices).” The US ranks first in this measure, at an average of $51,147 USD a year. Canada comes in 13th, at $34,421 USD, meaning that the average American is, at the end of the day, $16,726 USD better off than the average Canadian.

Over $16,000 USD (nearly $24,000 CAN) is no small chunk of change, and this would seem like a slam dunk for the argument that life is better, economically speaking, in the United States. But note the word “average” in the paragraph above. Now cast your mind back to high school math class, and try to remember the difference between “average” and “median”. As I’m sure you remember, “median” refers to the midpoint in a distribution of numbers. So “median income” refers to the person who has exactly the same number of people making more and less money than them.

A look at median incomes produces a different picture. In a 2019 paper from the Centre for the Study of Living Standards, entitled, “Household Incomes in Canada and the United States: Who is Better Off?”, Simon Lapointe drew attention to this distinction. Adjusting for Purchasing Power Parity (a way to account for the variable costs of goods and services in different countries), the average household income in 2016 was almost $83,000 USD in the US and about $74,500 USD in Canada – in other words, about 10% lower in Canada. But in the same year, the median income in the US was almost $59,000 USD, while in Canada it was about $59,500 USD, or 1% more.

How is this possible? Basically, there’s more income at the upper end of the spectrum in the US, skewing the average higher. It’s well known that the US has more economic inequality than Canada – or anywhere in Europe, for that matter – with 47% of income going to the top 10 percent of the population (versus 36.5% in Canada). So all those stats showcasing higher average incomes in the US are in reality just showing higher incomes for top earners.

Another way to look at this is how income is distributed across the population. Lapointe sliced the population of each country into 100 equal parts, from the lowest income 1% to the highest income 1%, and averaged the income of each part. He found that “Canadian households in the bottom 56 per cent of the income distribution are in fact better off than American households at the same point of the income distribution”. And keep in mind that this analysis doesn’t take into account all the government services Canadians enjoy for less cost than Americans, likely making the financial situation for lower and middle-class Canadians even more favourable.

This gets to an essential truth about an important difference between Canada and the United States: Canada is a better place to be if you’re poor or middle-class, while the US is better if you’re rich. In the States, it’s easier for the rich to get richer, and their wealth can buy better health care and education than what is available in Canada; but if you’re poor or middle-class, life is more of a struggle. In Canada, it might be harder for the ambitious to get ahead, but for everyone else, life is easier.

The “American dream” has always dangled this tantalizing possibility of getting fabulously rich in front of its citizens: with healthy doses of hard work and talent, anyone can elevate themselves into the top 10%. The Canadian dream, less articulated but implied, is more about the idea that anyone with a decent work ethic can achieve middle-class comfort and security. Needless to say, the Canadian version, though less exciting, is much more attainable for the majority of people

This accounts for at least part of the well-documented “brain drain” from Canada to the US. The very talented in Canada often head south to achieve levels of fame and fortune unavailable to them in their homeland. This results in a certain degree of mediocrity to Canadian culture; the people who remain here are often not those most driven to high achievement (with many notable exceptions, of course). The departure of these high-ability workers also contributes to the gap in GDP per capita and productivity observed between the US and Canada.

However, the brain drain appears to have been slowing for the past couple of decades. In the first ten years of this century, Canada experienced a net loss of about 15,000 permanent residents on average each year to the United States. But by 2021, the net loss had hit a record low of 3,339, with 11,955 Americans emigrating to Canada and 15,294 leaving Canada for the US. While the net loss is less, it should be noted that it is significant that it exists at all, considering the much larger population in the US – all other things being equal, you would expect a net gain of immigrants to Canada.

But perhaps a net gain is on the horizon. Since the beginning of Trump’s second term, the Canadian media has been running stories about some of our most famous human exports moving home, from comedian Shaun Majumder, to Pink Floyd music producer Bob Ezrin.

Americans are also feeling the call to migrate north. In the first 24 hours after Trump’s election victory, Google searches for “move to Canada” jumped by more than 5,000%, as “Trumpugees” contemplated relocation. Three high-profile departees to date are all Yale Profs jumping ship to the University of Toronto: power couple Marci Shore and Timothy Snyder (author of “On Tyranny”), and Jason Stanley. Three big brains who may be the beginnings of a significant “brain gain” for Canada, as Trump attacks higher education in the US. American doctors are also looking northward, and Canadian medical superstars, like heart surgeon Marc Ruel, who had been offered a job in the States, have decided instead to stay put.

People voting with their feet is perhaps the best indication of preference for where to live, and the balance may be beginning to shift in Canada’s direction.

Growing up

The question of whether Canada or the US is a better place to live probably has a lot to do with stage of life. The near majority of 18 to 34 year old Canadians who said they would prefer to become US citizens are likely less persuaded by cheaper health and child care in Canada, and probably more focused on “making it” in their careers – and the US is a more enticing place for that priority. Also, attachment to place tends to grow over time. When I was young, I was quite willing to live anywhere other than Canada. Only after travelling to some other places did I gain a greater appreciation for where I am from. That’s why seniors tend to be the most patriotic.

Regardless of which is the better country to live in, the mere fact that a large number of young Canadians believe they would be better off in America shows if nothing else that significant differences do exist between the two countries.

One country, born in a revolution against its colonial parent, chose personal freedom as its defining feature. “Live free or die”, the New Hampshire motto, emblazoned on its licence plates, is its starkest expression. The other country chose to sacrifice some personal freedom for “peace, order, and good government” – the famous phrase from the Canadian constitution that seems to define our approach. Over time, “good government” has come to mean a government that looks out for everyone, with an array of support programs. Government is generally seen as a force for good in Canada. In the US, on the other hand, there has always been a strong element of mistrust in government. Libertarianism, Ayn Rand, and Friedrich Hayek all found fertile ground there, propagating the “Road to Serfdom” notion that government was, at best, a necessary evil, and should be minimized as much as possible – focused on protecting rights, especially property rights. Any government support, these people argued, would lead to an inevitable slide into totalitarianism. Government was seen as the antithesis to freedom.

I think we can all agree that individual freedom is desirable; no one likes to be told what to do. But can you have too much freedom? We can all think of instances where we’re overwhelmed by choice and wish there were at least some constraints on us. And what do we sacrifice when we put freedom above all else? Just look to the US for the results of that experiment: high poverty levels, unrestrained money in politics, and gun violence, to name a few outcomes. The homicide rate in the US is 6 per 100,000; in Canada, it’s just 1.2. Ironically, the home of the free also has one of the highest incarceration rates on the planet.

Europe, especially Scandinavia, has charted a very different course. Finland taxes its citizens heavily, but has topped the World Happiness Report for eight years running. People there have less freedom to spend their money how they wish, but feel more economically secure. If money can’t buy you happiness, perhaps security can. However, some Europeans seem to move to North America to escape thickets of legislation that can leave people feeling overly constrained.

Canada exists somewhere between Europe and America politically. Culturally, we lean more American, but politically, more European. We strike a different balance between freedom and security than that offered by either our southern or our transatlantic neighbours. Partly this has to do with prairie populism, which in 1930’s Alberta ignited a politic party that eventually evolved into the left-wing New Democratic Party. (Ironically, modern prairie populism now drives the right.) Canada is atypical for Westminster-derived first-past-the-post democracies in that it has more than two major political parties, and the NDP, while never forming government federally, has historically exerted a gravitational pull to the left on the centrist Liberal Party. (In the US, third parties have been actively discouraged by the two main political parties, neutering this possibility for more progressive politics from the get-go.)

Then there’s the French influence in Canada. Throughout this article, I’ve made a point of mentioning how Quebec has a more interventionist government than the rest of Canada. Without the influence of Quebec, I suspect Canada would be much more similar to the US. You can trace this influence back to France, and the different political culture that developed there compared to Britain. The British tradition placed greater emphasis on personal liberty, the French on more collectivism. Canada inherited both these traditions and created a new blend – a concoction always influenced, now increasingly, by its third founding nation: the First Nations. What other nation combines these three influences?

Is it a good mélange? I tend to think so – but I’ve never really lived anywhere else. I know I’m a product of the very system I’m trying to look critically at, but the balance between personal freedom and economic security seems pretty good to me here in Canada. This, as I see it, is our core identity: this particular balance we strike between freedom and security. That, and how we offer this balance to immigrants from around the world.

Canada has a chronic inferiority complex. I guess that’s not surprising, living next to the most powerful country in history. But on the world stage, Canada is no midget. We are the 9th largest economy in the world. At 40 million inhabitants, we’re not that far behind countries like France and the UK, both in the 60 millions. And we’re growing faster, likely to surpass our parents by the 2070’s.

Canada is the second largest country in the world by landmass, controlling vast amounts of natural resources. In a warming climate, our image as a frozen wasteland will transform as we become one of the most habitable places on Earth. No wonder the United States is once again greedily eyeing us up. We will have to start acting more like a country our size, and look for friends outside of our immediate neighbour, if we are to survive this new attention from an empire rapidly devouring its own liberal institutions in favour of a fascistic regime.

That begins with recognizing our distinctiveness, what ties us together, and owning it. We’re far from perfect, but we’ve got a pretty good thing going here – and looking better by the minute, as other democracies around the world slide into xenophobia and authoritarianism. Canada has the potential to become a bastion of liberal democratic resistance to this onslaught, taking in political refugees from the US (an intensified redo of the Vietnam War’s draft dodgers), and allying with like-minded nations. Taiwan, South Korea, Finland, and the Baltic states all provide examples of small countries who have survived and even thrived for decades living next to malevolent authoritarian regimes. We can too – but we will need to believe in ourselves, and inspire others to believe in us.

We also need to make life more affordable – especially for young people currently shut out of the housing market. And we need to do that not just through our reflexive turn towards redistributive government programs, but also by strengthening our economic performance. We’re blessed with a lot of land and natural resources, but we need to push further beyond our tradition investments in hewing wood and hauling water, and move up the value chain, to become a country that can truly look after its own. Build Canada has been putting out some good ideas around this lately.

Trump’s threats seem to have awoken this country from a long slumber. It was the cancellation of a free trade policy and threat of annexation at the end of the American Civil War that spurred Canadian Confederation nearly 160 years ago. Now history is repeating itself. I’m hoping this latest round of aggressive talk from our unstable neighbour will push us to double down on what we have so far created here – millions of people of different backgrounds coming together to protect freedom, but also to make sure that no one is left behind – and to take it to the next level, forming a stronger union.

A bracing wind in our sails, a warm jacket to protect us from the cold, and open arms to the world – with elbows up against anyone who tries to threaten what we are in the process of co-creating here. That’s an identity I can get behind.

A good read, thank you Sean. A lot of thought and effort has gone into this piece. One point of clarification re: your comment: "So there it is: free health care, multiculturalism, indigenous reconciliation, and bilingualism. These are the four pillars, according to our new leader, of Canadian identity." I don't believe it was ever Carney's intention to suggest that these are the four defining characteristics, or "pillars" as you describe them, of Canadian identity. Rather they were provided as examples of (and there are many morw) Canadian policies and laws that reflect the underlying VALUES we share and hold dear as a people and a nation. It is these values that define and distinguish us as uniquely Canadian. A fine point but an important one, I believe, at this point in our history when we are being forced to take a long hard look at our values, examine the extent to which we as a people share those values, and are willing to hold onto and collectively fight for them.

Bless you Sean for this exhaustive research of the Canada/American profile. What I would add, and before any calculation of revenue, is the comparison of comfort level, given the U.S. gun culture. Having family who live there (part of the brain-drain phenomina, and then having the children choose to stay afterward), I know first hand the sacrifices people make, afluent people, around the question of security, in order to stay in that big-bucks market. Other family members were tempted but made a better accessment initially and factered-in the risk to life and property and wisely chose to invest their lives in our safe, balanced, middle-of-the-road Canadian society.......

Secondly - I take acception to the idea that we share language and culture with the U.S. I will conceed that on the surface we share something of a language with the U.S.; that being English. But to live there is to quickly realise that they have long since abandoned English as it was first introduced. (And French, zero). Your accessment of culture I reject outright. The America culture that I find (the American dream) revolves around having more than others, by whatever means. And their sexual exploitation of woman, I believe, is unprecidented in the world.....

So - No rhyme on culture there....

Those are my thoughts!